“The Hidden story”: Life as an Indigenous Ahwari person

Growing up, no one has ever told me that I have the blood of the ancestors who spent their lives scramming through the reed forests in the Mesopotamian Marshes to survive, but I've always touched that feeling; my veins were branched like sugarcane, filled with ancient stories; the wounds along my body are sacred havens for the secrets of my people, the traditional tattoos, and the stories about odd blue eggs within reeds while casually biting the corner of hot bread that was made from rice; the water they drank from where kids and hunters swam In balance and harmony, Sunlight reflected on a yellow cottage, its color the purple and blue at the dawn of the day and the warm sunlight until the red sunset, this isn't just imagery of the harmony between humankind and nature, it's an expression of the alienation. Alienation by feeling that we have become detached from the past where everything in nature seemed as it should have been, I don't know when this paradise has been destroyed, 40 years , 100, maybe one thousand years ago? All I know is that it was always there, carved down into the pathways of my memory.

What I was taught instead was the brutal story of the people who passed the riverside like migratory birds. They ended up in deserts and strange cities. And how, once they arrived at their destination, on the other side of the river, their wounded feet were chained; "Your home has vanished," they were told, right before their tongues were cut, because no one wanted them to tell this story, to enlighten their children, and to tell the world what they had gone through. Their kids were destined to live in despair and poverty, and the yearning for a home that's long gone by now, leaked into their blood. The home they once played in turned out to be a desert, with a blood-filled pond. The men were buried alive, their hands bound. They dug bigger graves for women with their nose rings and red hands that were colored with henna, for the grave had to fit them and their big pregnant bellies, As for us youngsters, we lived with our words imprisoned in our throats. Boys and girls were buried, and all that remained were a few handcrafted necklaces and unmarked tombstones. while the earth dried. While the soil dried, the planes ate children like a voracious pig.

The story says in the end, that these people have always come back to their land, because they die without the water, they’ll rebuild the huge Mudhifs by the reeds while they know it’s their only ally and everyone else are potential enemies.

I lived the heritage that my ancestors lived; not the local food and the traditional dances, but the heritage of discrimination, The majority of my family immigrated and survived the ethnic cleansing, while the others died or were subjected to torture, forced settlements, and cluster bombs. I've learned what being strong means from the women in my family, My grandmother saved her children from drowning in a flood while carrying her oldest son's body, she rebuilt everything while grieving her loss, and she struggled to live as the government kept purposefully flooding her home. My mother, on the other hand, is the reason we were able to withstand poverty and war.

Soldiers took the women's jewels to support the purchase of weapons. Ironically, the same weapons were used to kill them. Standing up to the government was a suicide mission because of the massive amount of money that our government received from oil companies and conscription.

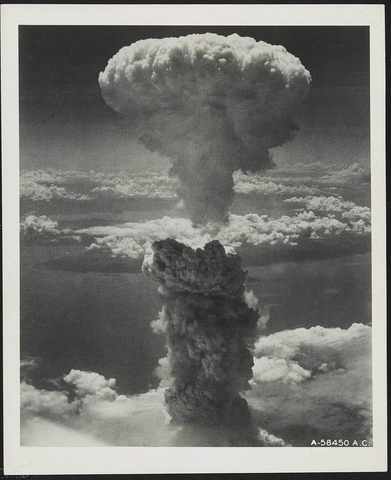

During the Gulf War, khamisiya the small town near Hammar Marsh, where armories are spread throughout, was blasted with depleted uranium by the Alliance Forces, exposing every single member of the family to ionizing radiation. The EOD carried out a demolition operation, resulting in the formation of a massive mushroom cloud, the effects of which continue to have a devastating impact on the health of current and future generations.

For many years, I've been thinking about the mushroom cloud, seeing it expand into an umbrella that curses us all. Six years ago, my grandfather died. Doctors told him that his body had been radiated, but he couldn't afford the treatment, so he became paralyzed and died. My other grandparents died in more horrific ways, my mother collected illnesses like lottery tickets, followed by my sisters and me. Reading anti-cancer medication prescriptions was not a pleasant experience, I knew I had a generational illness, but I never expected it to worsen so soon. When I was 10 years old, I had to have surgery and couldn't walk for a couple of months. I felt it was the worst torture someone could go through, seeing oneself bleed and suffer, witnessing my cousins have their fingers chopped due to birth defects, and on top of it all lied the unknown future.

I had this idea of writing my story but I wasn’t sure as it’s something that I live everyday and the story have never ended, but I thought of writing the story that is already ended with the people who lived through Genocide and ethnic cleansing, and if we don't say it, our loss will be tragic, I won't replace my words for silence anymore, I will speak out loud, with all my voice, with all pride, because I’m Ahwari, every single day, and that’s resistance by its own.