“Outside the Garden of Eden”: The Ahwari people and the conflict with the Modern State

At a time when we are witnessing environmental threat to the marshes, and the 30th anniversary of the Ahwari genocide and the Draining of the mesoptamian marshes, it is worth shedding light on the relations of the modern state with the Ahwari people since the beginning of the 20th century through an analytical look at the policies that shaped this relationship in several stages, The Ahwari people are an indigenous ethnic group in the delta of Mesopotamia characterized by a unique culture and history, which caused them to be subjected to historical persecution whose features have emerged after the First World War.

The War on Water and The Slave Trade

Because of the unique ecology of reed forests and complex waterways, the marshes became a refuge for those fleeing slavery during the era of the Abbasid Caliphate. The early liberation movements from slavery had been headquartered in the marshes against the Abbasid Caliphate in 869 AD and grew to rule parts of southern Iraq for decades, by the same slaves brought to work in the fields of southern Iraq amidst the labyrinth of reeds. Fugitive communities throughout history around the world have sought refuge in wetlands much like the marshes, such as the Tofino people who fled to Lake Nukoi to escape the slave trade. Iraq’s Marshes have been no different for those who seek its refuge. Iraqi opponents called the marshes “our Sherwood Forest” after Shi’a insurgents began using the marshes as a base to hide from government forces. Saddam Hussein resented the Ahwaris especially, because they offered a unique form of asylum to those seeking refuge and aid in the marshes, and because of their participation in the 1991 Uprisings. These factors fueled a violent rhetoric of ethnic and sectarian supremacy that ultimately ended in the extermination of the marshes.

The destruction of the marshes did not begin in 1991 or during the Iran-Iraq war, it began at least a century before then. The marshes were divided into two parts by the Sykes-Picot Agreement, the largest part amounting to 70 percent of the total area in Iraq and the other amounting to nearly 30 percent of the total area in Iran. The demarcation of modern borders became the first form of drawing the relationship between them and the Iraqi state, which was on its way to independence. For thousands of years, the marshes emerged as a stateless region similar to what James Scott describes in his book”The Art of Not Being Governed”, The region was hydrologically and physically impenetrable, a natural haven for slaves, defectors, and fugitives – destroying the refuge of opposition rebels was one of the main reasons for draining the marshes.

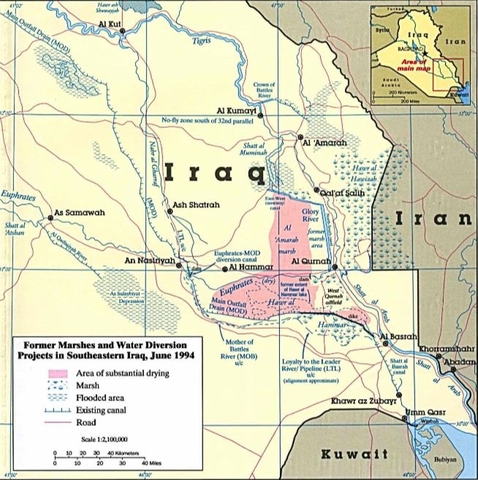

Location of the Mesopotamian Marshes between Iraq and Iran.

Displacement and National Development

The Ahwari people lived in relative isolation until World War I when increased trade and labor migration caused greater contact with the remaining community. However, during the emergence of the Iraqi state Ahwaris were considered to be a part of the “other” side of the nation. The marshes became known as the back garden of the state, where nowadays tourists would be hosted to polish the image of the government and generate economic growth, while toxic sewage was often dumped in and the water quota was constantly cut off.

The educated went to Basra and Baghdad, where they were not given work, lived in poor neighborhoods, and were persecuted by the police. As Wilfred Thesiger described in his book: “The Marsh Arabs”. ”As for the tribes’ gatherings, they inhabited the city of Thawra (Sadr City) in Baghdad, which for decades remained called the city of Saraif. It is made up of houses destitute of infrastructure and isolated from the city.” The residents of the marshes began to migrate to it after the construction of the Kut Dam in 1939, and this was the beginning escalation of the waves of displacement from the Marshes that would follow, the city of Thawra was later built with different engineering maps dedicated to the migration of villagers, which some architects described as an engineering disaster dedicated to the provisions of the government’s grip on the city.

Before the demarcation of the Iraqi borders by colonial Britain, the Ahwari people were classified as a distinct marginalized community, which had entered through the process of colonization and modernization of Iraq since the modernization schemes led by Britain in Iraq in the fifties and the introduction of methods that tighten the grip of the feudal system to end the local subsistence economy, Where the same tribal administration system used in Balochistan in South Asia, was introduced, Their environment has been a target of depletion to make way for infrastructural development such as the Nasiriyah Dam and the Rumaila oil field, the British-controlled Iraq Petroleum Company produced films and photos depicting the marshland as a “living reminder of the past.” This depiction of Ahwar and its people is adjacent to images of water infrastructure projects and oil refineries. The word "Ma'dan" was synonymous with "pre-modern".

Through developmental plans in education and modernization, our culture and its various aspects began to be associated with the past or pre-modern Iraq. The education and reconstruction systems were structured in a way that denied our oral and material culture and created a state of denial within our cultural identity.

Environmental Genocide and the Plan to Destroy the Marshlands

The destruction of Iraq’s marshes and the extermination of its people has been described by NASA as "one of the largest environmental disasters in the world". Most accounts, including the constitution of Iraq, attribute this dual genocide to Saddam Hussein's campaign for sectarian domination and revenge against the Shi’a, especially after the crushing of the March 1991 Uprising, but in a paper published by the International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, researchers gave a different assessment of what happened in the marshes and indicated that the destruction was, in fact, the intended outcome.

The despair of war is more than just sectarian hostility, which is the same reason that led Saddam Hussein into multiple wars, playing the chords of war and protection. The plan was older than the Gulf War, British Mandate officials were the first to try to drain the Marshes. The government’s agricultural plans for the Marshes date back to the early ‘50s during the royal era. It included a large project that began in 1953 and was known as the Third River Project and was reduced to a facade in 1963 and ultimately revived in 1991, but Saddam Hussein in turn developed it carefully. Other scholars have argued that the developed drain plans began much earlier, namely since the Iran-Iraq war 1985, but the order of the destruction plan, the genocide had begun being carried out since the 21st of April 1992, Ali Hassan al-Majid, cousin of Saddam Hussein and head of the Anfal genocide campaign, supervised the creation of a hermetic cordon around the Marshes, the environment itself identified as an enemy to be overcome in the context of cracking down on insurgency. Later, the Iraqi constitution of 2005 shows how the Ahwari people’s experience of genocide and displacement was erased, no mention of the marginalization and dissolution of the political identity of the new group, the lack of legal recognition for the existence of the group, the genocide, or the cultural rights of Ahwaris.

A 1994 map of the Mesopotamian Marshes with the pink zones showing drained areas.

After nearly nine months of round-the-clock shifts, the Iraqi government officially announced the opening of the Saddam River (the Third River) on December 7, 1992, in the presence of Saddam Hussein himself, it was celebrated as a victory for Iraqi technical prowess. Extensive drainage resulting from the construction of the Third River was just the beginning of further draining the Marshes and depriving them of the Tigris and Euphrates waters. At least four other major drainage channels were completed in 1993 and 1994: the Qadisiyah River, the Umm al-Maarik River, the Al-Izz River (Al-Izdihar), and the Al-Izdi River. Many dams were built to prevent backflow and other dams were also raised. In addition, the Hammar and Al-Hawizeh extensions were extensively divided by dams, and by a few years the largest wetland ecosystem in West Asia had become an arid desert.

Saddam river or the third river Iraqi postage 1995

In December 2002, Human Rights Watch published a paper detailing the grave crimes committed in Iraq during the 1980s and 1990s and urged the establishment of an international tribunal to prosecute the perpetrators of genocide and crimes against humanity, after orders were issued to plan to kill tens of thousands in the marshes through summary executions and indiscriminate bombings of residential areas in towns and villages. There were also persistent allegations that the armed forces were using napalm and gas in these attacks. Tens of thousands of others were tortured, forcefully ‘disappeared’, raped and imprisoned. Young men were executed in the streets, homes, and hospitals, and relatives of suspects were ill-treated in order to force them to Disclose the whereabouts of those wanted by the authorities, poisoning the water and burning homes as punitive acts and imposing an economic siege on the residents of the marshes preventing them from trade and government rations. In that time, nearly half a million people were expelled from the marshes, their historical homeland, to Iran and other regions by draining them with dams and canals, while at least 100,000 people became internally displaced in Iraq. A portion of the population was subsequently forcibly transferred from their original villages to settlements on dry land on the outskirts of the marshes and along major highways to facilitate government control over them. Discriminatory legislation was put against them, and they destroyed the archives of the marshes, archives that were already suffering from government bans and strict censorship on printed and published materials.

Completing the Destruction: Housing Plans for Forced Displacement

The Commission on Human Rights showed subsequent developments and stated that "the Iraqi government has in fact succeeded in implementing a much more ambitious plan, culminating in the almost complete elimination of the indigenous population through brute force and the systematic destruction of their economic livelihood and natural environment." These events were followed by new orders to prevent the return of the population and to complete the implementation of the destruction plan, including the large-scale and deliberate destruction of homes and property through dredging or burning. This was done systematically after bombing the targeted villages. Crops and other plants were set on fire, livestock was deliberately killed, and water mines were planted in the remaining shallow waters used by the residents. Water mines were responsible for dozens of civilian deaths and injuries, as well as the deaths of a large number of water buffaloes and livestock on which much of the local economy depends.

The special rapporteur reported to Human Rights Watch that the ration card system and denial of treatment continued to be used as a means of enforcing “loyalty” to the authorities or as a tool meant to be used for collective punishment of Ahwar’s tribes that were prejudiced as “hostile”. Seeking medical treatment in clinics or state-run hospitals meant risking arrest. Whenever possible, the wounded would be smuggled to Iran for treatment, but the journey was dangerous, and some did not survive. Civilians who were sick or in need of medical attention faced similar problems, especially after the government began removing medical stocks from hospitals and clinics that were close to the marshes, including those in Basra, Nasiriyah and Amarah, and moving them north. In terms of tightening the economic blockade imposed by the government on the region, this necessitated a complete ban on the transportation of foodstuffs, refined petroleum products, and medicines the Marshlands, it was reported that army patrols searched travelers to the area and seized or destroyed any food deemed to exceed the needs of the family.

The authorities deprived the families who refused to move to their monthly food supplies distributed according to the ration card system introduced after the imposition of UN sanctions. Exacerbating an already dire situation mainly because of the inaccessibility of the marshes, some of the people were not formally registered with government records and did not have the identification cards needed to register for their share of rations.

In April 1992 the Iraqi National Assembly approved a new housing program. According to the then-Iraqi Parliament Speaker Saadi Mahdi Salih, the government's intention was to relocate several thousand of Ahwaris to homes constructed along the Basra-Qurna highway and other areas to bring about a demographic change. The housing plan was justified as, “to provide them with electricity, clean water, schools and medical care” and to, “make them good citizens.” When discussing whether Ahwaris would be consulting on this forced relocation, the response was, “you will be given the choice to move or stay, whether we say it is mandatory or optional, is not important to them.” The parallel between the Kurds and the Ahwari people was not lost on the Speaker of Parliament, referring to the Kurds, “at that time we evacuated these people and put them in compounds and provided them with amenities, but for political reasons there was a dispute against us in the West regarding the people of the Marshes, the West should help us move their homes and build schools for them and improve their health conditions instead of providing criticism as America nearly wiped out the Native Americans from the face of the earth, and no one batted an eye.”

The forced resettlement program in the Marshes was accompanied by a campaign of ethnic cleansing, including indiscriminate attacks by artillery, helicopter gunships and fixed-wing aircraft on villages, as well as the arrests and executions of civilians, particularly tribal leaders, the destruction of property and livestock, and the demolition of entire villages. Entire families were targeted when they refused to evacuate their homes. The waves of arrests followed reports of mass summary executions. Among the reports received by Human Rights Watch at the time was one incident involving the execution of about 2,500 people in August 1992. Victims, including women and children, were arrested in Chabayish with captured fighters, according to testimony obtained by Human Rights Watch, including the testimony of a survivor who was taken to an army camp in northern Iraq where they were executed after a period of about two weeks.

Likening the plan of destruction in 2015 as similar to previous experiences in which the same modern counterinsurgency tactics were used in the marshes from all axes that cut off the local economy and caused famine, it said: “What happened in the marshes was not just an act of war then, but a strategy for development and social improvement” what Samuel Huntington called “forced draft modernization,” the state intervened directly in the human environment using advanced technologies to forcibly change the way populations interact with the natural world. Similar stories can be told of British and German uses of concentration camps and “hunger wars” in Southern Africa, the Soviet eradication of Kazakh nomads, the US clearing of foliage from Vietnamese rice fields and Portuguese attempts to defeat the rebellion by building a dam in Mozambique. Third World countries have since adopted similar tactics, as in the "Beans and Bullets" campaign and the Guatemalan Genocide of 1982 in the Central Highlands.

Propaganda and speeches of Saddam Hussein

The media is an integral part of the cultural processes that produce social meanings. By analyzing the discourses conveyed through newspapers, we can follow the different methods of producing government propaganda towards the Ahwari people,, The Baath Party regime published a series of articles in its propaganda newspapers “Thawra”, “Jumhuria” and “Qadissiya”, Journalist Durgham Hashim was executed when he objected in another article, and In one of the articles the genocide was justified as “a necessary stage for the rise of the nation”,This was reported a paper written by Jon Fawcett and Victor Tanner in October 2002 titled “The Internally Displaced Persons of Iraq,” published by the Brookings Institution and the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University. The Iraqi state-owned media preceded the attack on the Ahwari people with a series of articles describing them as primitive “monkey-faced" people” and saying that they were not real Iraqis. Saddam Hussein no longer considered the inhabitants of the marshes to be actually Arabs, breaking the British and Arab national narrative that the Ahwari people are Arabs, and in terms of sect, the Shia were generally considered Iranians, according to his personal doctor, Saddam Hussein said the following things: "The people of the marshes are not real Arabs, they came from India with their black buffaloes 1250 years ago when the Abbasid Caliphs needed slaves, but they have not developed since then, they are not like other Iraqis, they have no morals, they lie and steal and they have no pride, their behavior is not like ours, women in particular are completely immoral and unprincipled, these people live an immoral life.” It was mentioned in one of the articles, “It is the habit of the people of the marshes to hold their hands on their chests with a bow, and that is the nature of the Ajams, not the Arabs.” It was said that their buffaloes are so indistinguishable from them that they have an intrinsically degraded nature, a saying similar to how Lawrence of Arabia described the inhabitants of the marshes in the midst of the formation of the Iraqi state. During the 16th interrogation session of Saddam's trial, a woman from the Marshes recounted the details of the treatment her family was subjected to at the hands of the Iraqi government. She said that they had nothing left and that they had to leave their homes with little possessions. Saddam laughed and asked: "What was it? That you owned before? Bundles of reeds!” During the 19th interrogation session he said that he had wanted to advance the way of life of the Marsh Arabs “so that they would not live like animals,” and that it was “a step in the interest of Iraq” and that “there is no historical value for Ahwar” and regarding the interest of the Iraqi government's environmental impact of draining the marshes he pointed out that "the Americans did not allow the American Indians to live as they were before colonialism."

Among all Saddam’s victims, Ahwaris did not receive compensation for their forced displacement and the destruction of their homes. The government considered the reed houses to be without official documents proving their ownership and therefore they were not considered real houses. Saddam’s answers during his interrogation illustrate the popular view that the Ahwari people are a group outside the framework of the state, that being in a state built on violence against your society is, in itself, a continuous violence perpetuated alongside and against the continuity of your existence. When the nation considers your society as primitive, hostile and disadvantaged, and your indigenous history as foreign, the force that forms the social hierarchical structure within this arrangement makes the development of the state stronger and harsher. Thus, your society will be the constant enemy and the natural sacrifice on the path of supposed progress, the roots of institutionalized racism re-emerging wherever a crisis emerges, revealing the state's true fragility and repression.